The Man Who Fell From The Sky

“Jake” Wilson recalls the Flintlock Disaster.

Hawkins Field, Tarawa Atoll. January 25, 1944.

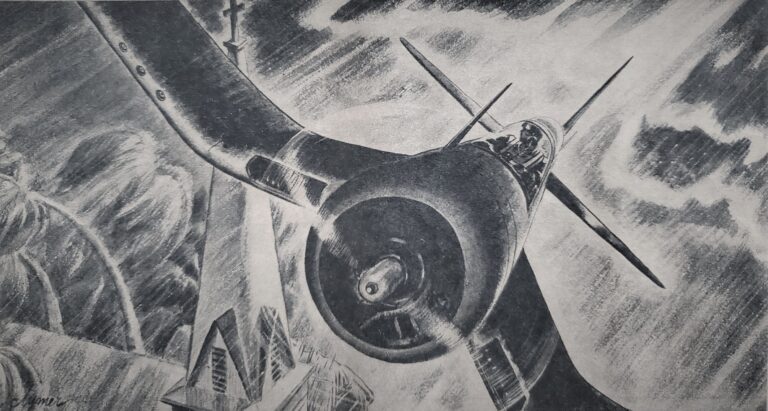

Twenty-four brand new Vought F4U Corsairs were readying for takeoff. It was expected to be a straightforward operation, a “milk run” to relocate the entire squadron in readiness for Operation Flintlock — an offensive to be launched against the Japanese. What happened that day, however, was anything but straightforward, and would go down in history as the greatest Naval Aviation disaster of WWII.

Squadron leader John MacLaughlin reportedly asked his superior for a navigational lead plane, standard procedure, but was denied. This set in motion a perfect storm of bad decisions, communication, and weather forecasting that would imperil the whole squadron, VMF-422 — “The Flying Buccaneers”.

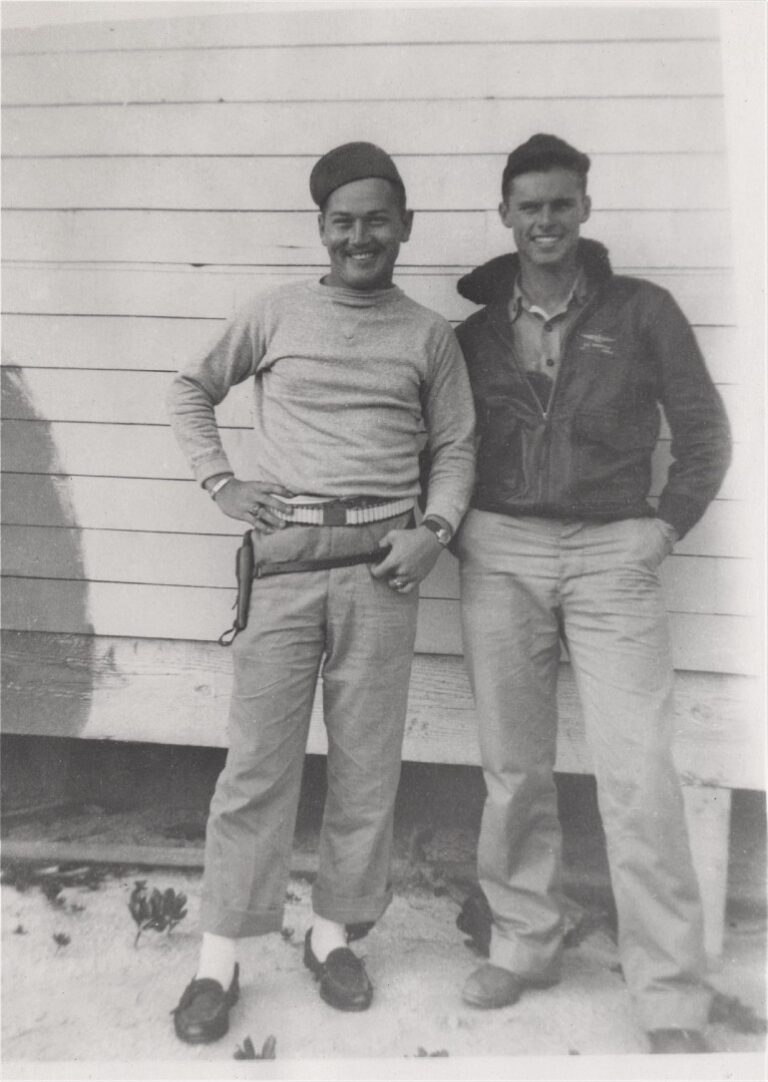

While the Flintlock Disaster has been well documented in Naval War Histories, little is known about Lieutenant “Jake” Wilson’s recollections, and of his experiences with the natives of Niutao where he crash-landed. But dad didn’t talk much about the war. The following is an excerpt from his journal.

Walter "Jake" Wilson. 1945

The Storm, Chopin, and Niutao

The mission was simple: Transfer 24 brand new corsairs to another island farther away from the Japanese. It ended up going from simple to harrowing.

I was just a kid flying a corsair. I’d only a few hours in her, “The Rapid Rebel.” We’d been trained in the F4Fs and she was a quantum jump in power and maneuvering. I looked forward to the relocation very much.

Felt like my blood was pumping harder than normal that day. I chalked it up to just being excited. One fella couldn’t start his machine so 23 of us took off headed to Nanuma [sic].

Perfect formations, like when the geese fly. My gauges acted up a few times but everything was going fine. Perfect day for flying without the Japs [sic] to irritate us.

I noticed a faint blue off in the distance. Mac radioed “Squall ahead!” — and we’d fly over it. Lickity split we were up against a giant wall of black. I’d never seen anything like it. We tried going over it. Then under it. No good. In no time we were inside it.

We tried to keep on our course but it wasn’t easy. I wrestled with the stick as 150 knot winds pushed me around like a piece of paper; my plane whistled and creaked and moaned, my gauges didn’t work, and I couldn’t see a thing. Radio contact was sporadic.

I didn’t know where I was and neither did anybody else. Soon we were zig-zagging through a cyclone at full throttle. They didn’t train us for this.

—

— It was playing. Chopin, in my head. One of the Grand Polonaises. I was startled at first; I wasn’t too familiar with Chopin but there he was, clear as can be — like I was at a concert.

My hand was going numb. I noticed I was gripping the stick too tight. I relaxed a bit. All at once I was thrust upwards and away from my formation. I couldn’t tell my altitude but G-forces told me I was moving at tremendous speed.

I was separated from the boys. I dropped back down to just over the water to find them. I could not. I was alone inside this black monster. Whoever was playing the Polonaise was banging it out now. Chopin and I zipped around for what seemed like 5 hours.

My instruments were no good, I couldn’t tell where I was going; everything was a jumble. There was only one thing I could do — keep flying and trust in God. At one point there was a break in the storm and I saw a blur of what looked like a corsair far below me. I banked hard and swooped down to follow him. Back in to the monster—he disappeared.

I flew best I could where my instincts told me. I fired off a few rounds of my 50 calibers. It felt good to shoot the beast that was tormenting me. I was exhausted. Then something, some instinct, told me to bank hard to the right and set her at full throttle and go straight as I could, for as long as I could.

Thoughts went in and out of my head. Perhaps I should’ve gone in another direction. Maybe I should’ve turned when I had that hunch to fly straight. My engine sputtered. Though we were trained to do it, I did not want to ditch her in the water. I must be close to Nanumea — but where is it?

Then more thoughts — Is this the time I would die? What would my mother feel? What would my sweetheart feel? Would I be a hero or … is this what I was put here for, to die inside a monster storm? Is God there — watching over me, right here, right now — in my hour of need? Somehow I could feel it. Somehow — I knew it.

Before I could finish my prayer a palm tree dashed past my starboard wing — then another. I pulled up just in time to miss the trees — and a church steeple. I could see no lnding [sic] strip and decided I must set her down, before I ran out of gas, while I still had time to choose where.

I’d grown better at seeing in the dark, through the mass of water slamming against my cockpit. I circled the island 3 or 4 times, a small atoll with no clearing long and flat enough on which to land.

I passed over a stretch of beach … there, I was trained to do this, I’ll swing around and approach again just to make sure.

Yes, it would work — if only there was a strip of land. But there was only beach. Beach it is! With wheels up I came in over the church. I tightened my straps and hit the flaps.

There was a terrible noise when I hit the surf. Not a bad landing. “What a marvelous machine!”, I rejoiced, as I unhooked my straps too soon. I hit my head on the instrument panel as she slid to an abrupt halt. Things got blurry. I must’ve blacked out for a second.

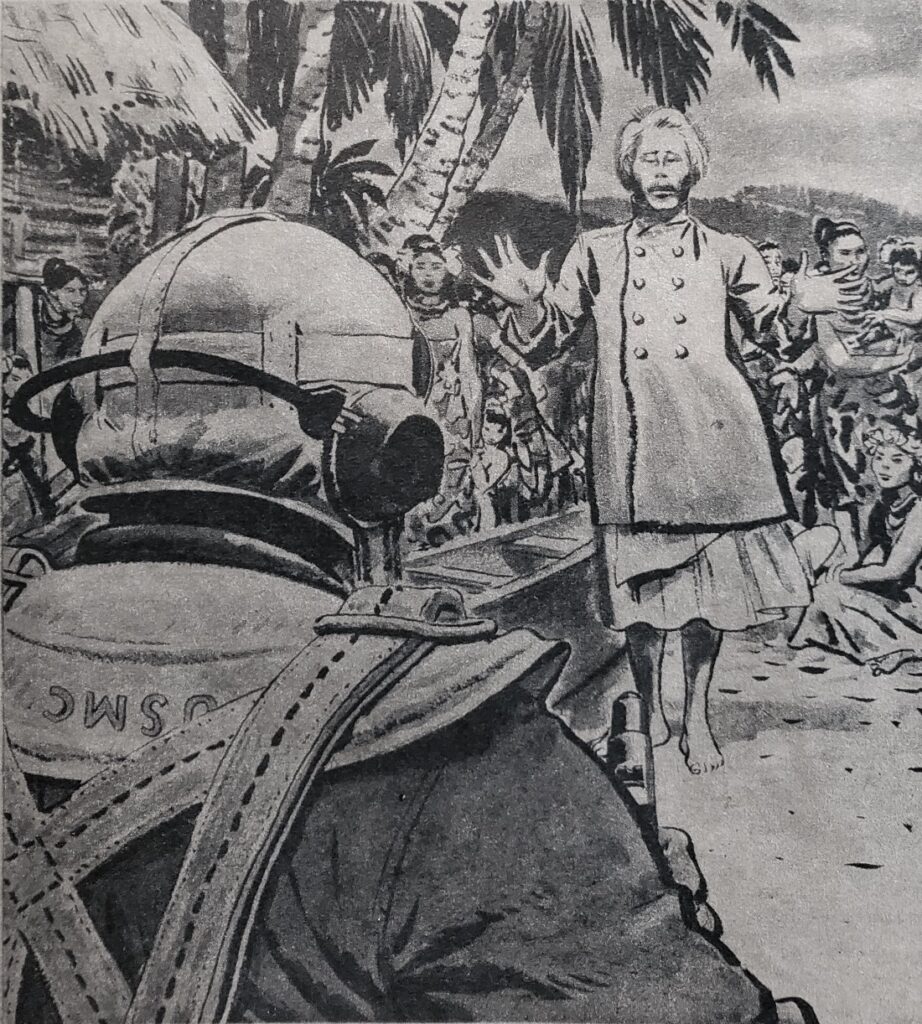

I jumped out of the cockpit, then saw a crowd coming toward me. I couldn’t tell if they were natives or Japs [sic]. And if they were natives I had no way of knowing they were friendly.

I pulled out my pistol and waived it at them threateningly. One of the leaders came to speaking distance and said, “Friend, Sir, American God’s man. We God’s man, too.’” Then the natives came closer. Things got blurry again.

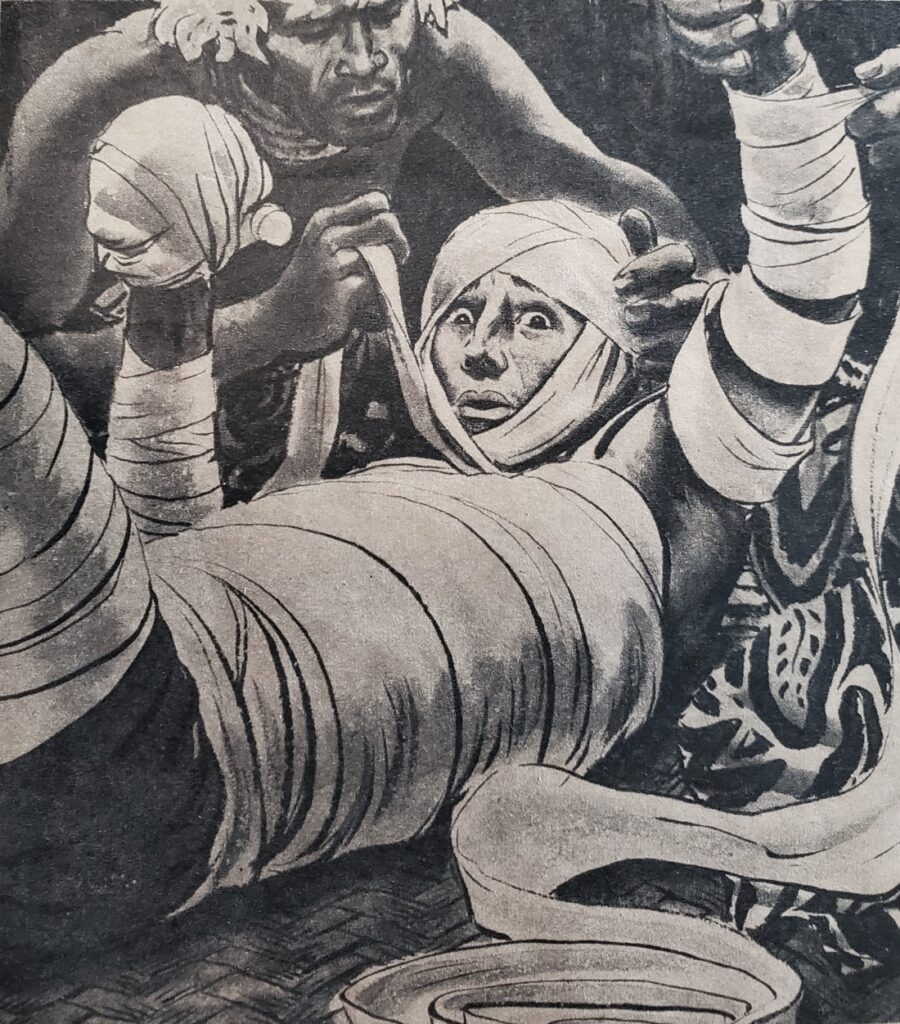

I woke up in the native chief’s hut. A native doctor was moving around me. I was unhurt, just a bump on my head, but the doctor insisted on wrapping me with white cloth. “No need for that”, I protested. The doctor mumbled, “We make you strong again”.

“Really, I’m okay”. But he was not to be deterred. “You drink”, he said, and handed me a clay cup with some hot, green liquid in it. I hesitated.

“Drink!”

I drank. It was bitter, but not so bad. Then he wrapped and wrapped until I resembled a man who had broken every bone in his body.

The chief was a very pleasant fellow. We got on very well. “Where are you from?”, he said in good English as the storm started settling down. We sat on the sand in front of a celebration fire surrounded by a throng of villagers.

“Mississippi”, I responded.

“Where is Mississippi?”

“Oh it’s in America”.

“America!”, he proclaimed. “America good. Japan bad. All of America is Mississippi?”

“Oh no, just part”, I said. “There are many states in America. They’re all different. But y’all have it pretty good here now?…”

“Yes. America came and drove off Japan bug. Japan, they were crawling on the ground, like bug. Dig tunnels, like bug. God make bug, bug good, but that bug He made mistake, no good.”

“Back home we used to get the ladybugs and sprinkle ’em over the beans to keep the bad bugs away”, I offered.

“I understand”, he said after pondering my words, as if I’d said something important.

After a few quiet minutes reveling in my present location, the sweet sound of children playing, the fresh air, and my good company, the chief spoke again.

“The Storm made you fall out of the sky. It brought you here.”

“Yes, it was a doosey. Never seen anything like it. I worry about my friends who were with me.”

“You go back to the Storm?”, he asked.

Looking around I could see only clear, beautiful skies. “No storm tonight”, I predicted.

“You will go back”, he predicted.

—

There was a radioman stationed on the island and he signaled HQ that I was here. People from all over the island were coming to see me. For some reason they were treating me like a hero. There must’ve been 100 of them surrounding the chief and me. I was asked to make a speech. I’m no good at speeches but the chief insisted.

“Well, I — just wanna say thanks, so much, to all y’all for your kindness. I don’t know what I’da done if I hadn’t found your beautiful island here, um — what is it called …”

They replied in unison: “Niutao!” The sound of all of them chanting the word was a lovely sonic experience.

“It’s a beautiful place you have here and I hope y’all don’t mind me stayin’ over too long. You saw that B-24 just now — one of my Army friends flew by to drop some food, candy and cigarettes for everyone. So, maybe we can repay your kindness with these small tokens. Well, that’s it, and — um, thanks again, so much.”

The chief started to growl. Apparently my speech wasn’t long enough. He waved his hands for me to continue. “Tell of Missippi!”, he commanded. Upon his words the people echoed, “Missippi” … so I proceeded to tell of Missippi.

—

During my stay I attended several parties thrown in my honor and was obliged to make several more speeches. I talked of back home, the World Series, Bennie [sic] Goodman, Artie Shaw, Charles Lindbergh … they didn’t know what I was talking about, they just liked the sound of my voice.

At the end of one of the parties I was summoned to the chief’s HQ. He told me he had some good news.

“Wilson, you must take a wife”, he declared.

“Oh — ”, I said, “that’s true, I suppose, but I’ll wait on that, thanks very much.”

“No wait!”, he retorted. “Old man no good for a girl. You take wife tonight.”

“Chief —”, I stumbled, “under the present circumstances I wouldn’t be around very long to be much good to one of the gals here, I …”

He didn’t seem to understand that I wasn’t staying. Or, if I did leave this tropical paradise I must be out of my mind — what, to go back to a world at war? He had a point. I made a mental note.

—

The party was for my betrothal, I must pick a wife. All of the young girls were there. They were pretty and they danced for me. The chief told me to choose after all had danced. I sat watching them go through their rhythmic motions. Man if the guys could see me now …

The natives had been kind to me. They’d given me presents and a body guard of 4 native police. I had a room half full of coconuts and 14 chickens. After this kindness I didn’t want to hurt their feelings. My head still bandaged, I feigned illness. This afforded me some time.

The next day a destroyer came to pick me up. With tears in his eyes, the chief bid me farewell. He asked me to come back as soon as I was done fighting. With tears in his eyes he bid me farewell with the biggest hug of my life, and so I left my friends in paradise.

A storm more dangerous than the Japanese claimed six of our pilots and 21 of our planes in a matter of minutes. I would lose more friends along the way in a conflagration I didn’t understand. And I would be required to kill people who were “the enemy”. It was expected of me.

I was just a kid who wanted to fly airplanes — a glamorous adventure. That was 20 years ago. Time has afforded me a perspective.

Reckless young men seeking adventure will climb in to fighter planes to go fight other young men seeking the same — to do what reckless old men seeking power would not.

After the war I stayed in California, crossing paths with mad men, musicians, and movie stars. At first it was everything I’d wanted. But soon I was swept away by a storm of a different kind — a glamourous [sic] but reckless life of booze and pills.

Still fighting the enemy — myself all along — one day I crashed.

I had survived the war — but I had not come out unscathed — I had been profoundly wounded by the loss of my friends who did not. There was no meaning, just sadness. I compensated with good times and drink.

I will always be indebted to a friend who suggested I stay at his house to sober up and get my life back in order. This opportunity, this respite in the eye of the storm — saved my life — my friend afforded me the necessary time to come to terms with myself, and what had happened.

I realized that the people who come in to my life are eventually fated to disappear. I can only love them, with all that I have.

When I search through what I am, and could ever be, what else is there for me to do — ?

But to do this, I must first love myself. I set about on this course. And, were I in the position to help, like my friend who helped me, I would.

I married my Mississippi sweetheart and became a minister. My speeches have shown marginal improvement and I do less of what is expected of me.

I never made it back to Niutao. One day? I often dream of it. The sweet smells. The good people there; how they embraced me — a stranger, who fell from the sky.

3 Feb, 1964.